By the time The Bell Jar was published, Sylvia Plath had already tried to take her own life, was in a psychiatric institution for months where she endured shock therapy, and would successfully take her own life in 1963 shortly after releasing one of the most substantial novels in American literature.

I don’t write that last phrase lightly. When Plath wrote The Bell Jar, women were still getting lobotomized as treatment for their mental illnesses. The mere conversation was taboo, and if you were unlucky enough to be a woman, you did everything to escape that label for fear of how both society and the medical profession would treat you.

It was in this environment that Bell Jar was written. With this semi-autobiographical story, Plath was channeling the spirits of novels like The Yellow Wallpaper by Charlotte Perkins Gilman or Villette by Charlotte Bronte. Plath took the essence of The Awakening by Kate Chopin and used her own life to depict the intense feelings of loneliness and depression that ultimately led the author to take her life.

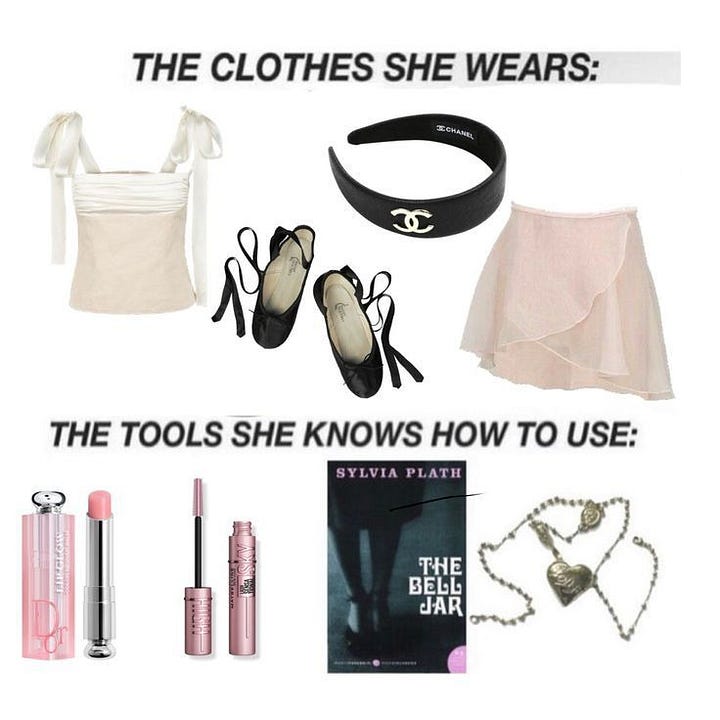

But judged by today’s standards, The Bell Jar sounds like a desirable lifestyle for today’s melancholic young woman who wants desperately to connect with anything that can be publicly identified. The novel has morphed into an aesthetic, a way for readers to describe a type of sadness or discomfort with their lives that they couldn’t name until they read Plath’s masterpiece.

Part of me loves that readers have connected with a piece of writing that is over sixty years old. The other part of me fears the oversimplification of novels, in particular novels with nuanced messages, is a frightening dynamic that is absent of any true connection or understanding of a piece of deep literature, and that lack of understanding can be dangerous for the future of the literary world, art in general, and for society as a whole.

Before you call melodrama, I want you to read this excerpt by a writer named Sophia Brousette speaking of this very same aesthetic:

“Sometimes it is hard for me to tell what came first — my Tumblr account or my mental illness. I would like to believe that I discovered Tumblr seeking to understand the disturbing emotions encumbering me in my pre-teen years; that my first pre-pubescent reading of The Bell Jar gave me a vocabulary for how I felt, that Marina and the Diamonds’ “Teen Idle” was an anthem for me because it was reflective of my experiences. I am not so sure anymore; If this would have manifested in such a deep a pit of gloom within me had it not been so romanticised in the media I consumed [sic].”

Did you read that last line?

That’s my fear, and not the ‘romanticizing by media’ in the typical way we’ve come to know media, but in the 2025 way where the most influential media are individuals, real people not a brand, and these real people feel close enough to us for their words to matter that much more, enough to reduce a tragic story of suffering into a cool “Sad Girl” trope that comes with a Lana Del Rey song and a “girl dinner.”

There are plenty of stories like the one from that excerpt. This is partly why I don’t think we should take it lightly that readers are engaging on a superficial level with literature that needs to be dissected. Most pieces of great literature allow you to engage on several levels. You can read the plot or storyline and understand the events. That’s surface, and sometimes that’s all you need to enjoy or dislike the novel. But in most instances, there are underlying themes that must be explored in order to fully appreciate the author’s writing, and I don’t just mean for literary novels.

You can read a story fantasy novel like Poppy War and come out of it with just as many allusions as My Brilliant Friend. Both share entertaining surface stories with magnetic characters, but if you only read Poppy War as an action adventure with a female hero and only read My Brilliant Friend as a story of friendship, you are fundamentally missing the point of those two books. And I don’t mean that superficially. You are actually missing the point and can not fully appreciate either of those stories unless you mine for the gold beneath the surface.

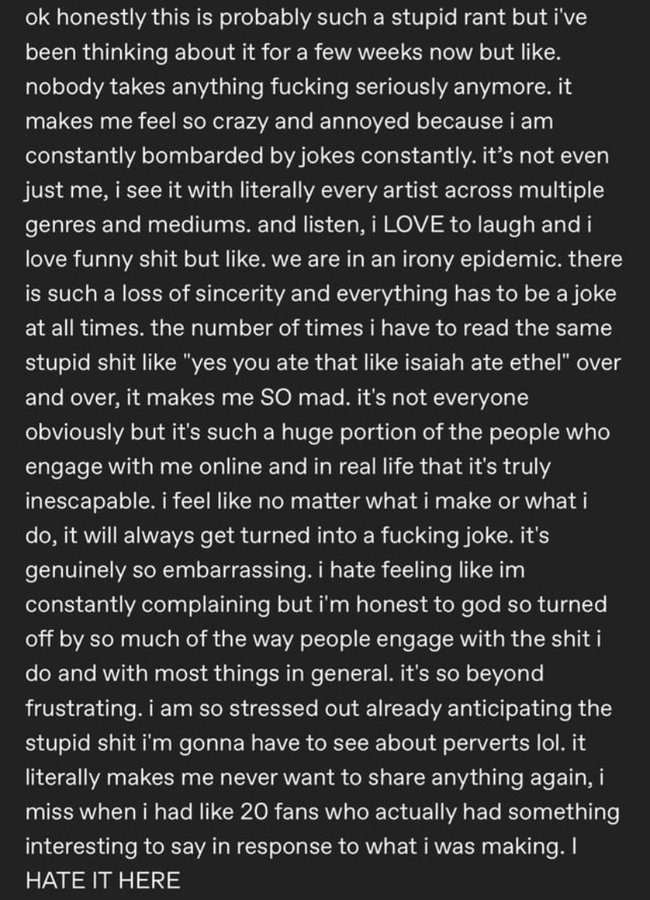

This trend of oversimplifying down to its most basic value is not just happening in literature. Read what musician Ethel Cain wrote on her Tumblr (before deleting it). For context, Ethel Cain is a newer artist who is referencing her album titled Preacher’s Daughter where she tells the story of a fictional character named Ethel Cain who is abused by her father and eventually cannibalized by her boyfriend who first sold her into prostitution. I mention that only for you to understand the depths this artist goes through with her storytelling. Here’s the quote:

You can’t get any more real than that. And this is an artist speaking directly to her fans. And it’s not like she’s begging for attention, she’s begging for deeper appreciation that goes beyond “Yaas Queen” or “She ate that.”

These are the consequences of reduction.

And this is why I fear for literature. Books require readers, lots of them. But maybe more than any other artistic format, it requires readers to engage actively as they flip from page to page. It’s this attention that I believe authors are counting on. It’s why we describe scenes the way we do, why we shift heaven and earth to build full characters, it’s why that thought the main character had on page ten makes so much more sense on page one hundred. These are the characteristics that are specific to literature that makes it truly unique, and if it’s not being acknowledged by readers, then what’s left for us?

And no, this is not a commentary on complicated books versus more straightforward ones. As I said before, all the best books are layered so let’s not go down that path. What I’m trying to get at is that if layers aren’t being appreciated, then it limits our ability as authors to tell stories. And any hindrance in creativity is problematic.

Let me give you an example outside of literature. According to a wonderful piece written by Will Tavlin, Netflix has been telling its screenwriters to cater to viewers who are casually viewing. More specifically, Tavlin says Netflix tells writers to make their characters, “announce what they’re doing so that viewers who have this program on in the background can follow along.”

Umm…what?

So now we’re catering art to people who aren’t even fully engaged? Even writing this right now, I feel so angry. Or maybe not angry, but really disappointed that the most prominent streaming platform in the world is purposely choosing to dumb down its shows and movies and for no creative reason at all.

Why I use this as an example is because if film is already doing this, is publishing far behind? If authors realize that the chances of getting your book turned into a film is made that much easier if you spell out parts of your story so plainly that there’s no need for the active attention I declared is what makes books so special, then how long until that becomes the standard?

To say it’s a slippery slope is an understatement. But it’s this kind of thinking that probably caused Ethel Cain to delete her post. Why piss off the casual fans that listen to their (Ethel’s pronoun) music while scrolling through their phones, commenting before they’ve had a chance to absorb any of its messages? Why anger the casual fans who just want to wave their arms to the rhythm and when asked to elaborate on why Ethel is their favourite artist, they say “That’s Queen Mamma.”

Listen, we all do a little pandering. I hope I’m not giving high horse vibes here. We want our stories to be accessible and there is absolutely nothing wrong with that. Again, this is more about the reaction to books than the books themselves, but I think it’s vital to talk about this because it’s the reaction to books that slowly begin to define those stories, those authors, and how society engages with art is a reflection of how others see themselves. That’s why I included that excerpt from Sophia Brousette at the beginning of this piece.

This stuff matters.

Let me end with another excerpt from Brousette:

“In many ways, once I found something to relate it to, my sadness drove me. It now had a meaning. It made me interesting.”

There are consequences my friends, real ones. But these are just my thoughts. What do you think? Is the oversimplification of books a real problem?

There are too many good stories and not enough good readers, listeners, and watchers. Shakespeare had to contend with the same systemic problem. By telling the a single story at different levels of appreciation, he created works that lasted for centuries. Maybe we storytellers have to be a little more realistic and stop blaming our audiences. Their plates are full. It's our job to seduce them and make them want to go deeper.

An extraordinary essay. A couple of times recently I entered into some literary discussion and got, “oh, the book has a theme!” Like, real surprise. That’s why Substack matters. We need this place to talk and learn about books, about literature, art, life. We need to peel back the layers of yellow wallpaper. Should The Bell Jar become so familiar it becomes a trope, a cliche? Damn straight, but not in such a way as Tale of Two Cities, where everyone knows the first few words and nothing else. The Bell Jar and all books that can teach humanity about itself on that level need to be taught, reviewed, discussed, read again five years later, repeat. This is how humanity grows itself into something worth saving.