My mind erupted.

I had just finished reading A Brief History of Seven Killings by Marlon James and couldn’t wrap my brain around the experience. James’ novel is a psychological adventure, a mind-bending blend of fantasy and suspense with historical fiction and a literary flavour I had never tasted in my life.

This happened about a decade ago and my first reaction from an author's perspective was “I don’t believe someone is allowed to write like this.”

My astonishment was mostly aimed at the fact that A Brief History had won the Booker Prize despite not having a main character, despite the amount of patois in the prose (patois is Jamaican dialect), and despite the fact that it was a black author from a small island writing about the turbulence of his birthplace beginning in the 1970s.

“Do I really have permission to write like this?”

That question loitered in my thoughts for months. When I considered permission, it wasn’t from the literal sense of the word. I know living in North America, we can technically write whatever we want. But my focus on permission was through the lens of what was and would be accepted and who that writing would be accepted from, and more curiously, how far was that writing allowed to spread into the world and be understood by so many.

In my own writing, I questioned the reaction of publishers and readers to me writing female leads in my novels. In subsequent interviews, it was the point that most interested interviewers. Although they praised my execution, they wanted to know why I thought I could pull it off, or if I ever worried that I might be treading dangerous waters because I am a man and how could I possibly get inside the head of a woman deep enough to create a believable character? Essentially, they were politely asking who gave me permission.

Permission is such a fascinating thing. I think back to the nineteenth century; to Currer, Ellis, and Acton Bell, names rearranged to hide the ugly truth that their true gender did not have permission. Their capacity for intellect elicited fear disguised as order, so pseudonyms were created for permission, as it was for Mary Ann Evans, shielded behind a name that was used so she could enter into the world of literature without the judgement her true identity would have conjured.

Permission is such a fascinating thing.

I think back to that seven-year-old girl from West Africa, piled onto a ship and sailed to the east coast of the Americas. Only good fortune landed her in a home where her master was progressive enough to allow her to be educated, and she was reading and writing in multiple languages by the age of twelve. Her potential for poetry was astounding enough for her enslavers to pursue publishing, but not in the Americas. It took another ship to London for the first African-American author to publish a book of poetry.

That was a long time ago. We don’t need to ask for permission in the same way today, correct? We should pat ourselves on the back because we are far more tolerant, far less sexist, less racist. We don’t imprison journalists for writing the truth and sharing that truth with the people of their countries, or force publishers underground for publishing books that go against the dictates of a state. No. We are beyond all that.

We don’t ban books that speak to a diversity of experiences that may seem queer or unfamiliar or represent a history that isn’t often acknowledged. We wouldn’t do that. This is the twenty-first century; we all have permission. Just like you and I have permission to say this book shouldn’t be written by that person because they don’t have permission to intrude on our culture, to appropriate our lives through words because imagination should be confined to experience.

Permission is such a fascinating thing.

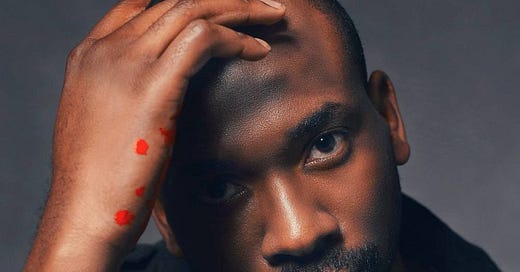

An interviewer once asked the late Toni Morrison why she doesn’t write about white people and why they are left out of her stories as main characters. When for my second self-published novel, I used a white girl for the book cover, my black readers bombarded me with questions and criticisms and accusations. In Morrison’s case, the insinuation was that she had been permitted into the club of popular authors but was not following the rules. In my case, the inference was that as a black author, I didn’t have permission to write stories outside my race.

In both cases, permission is being weaponized. In both cases, fuck permission.

Because sometimes permission needs to be taken and not asked for. James’ novel was rejected over eighty times. He tossed his manuscript in the garbage and it was only at the insistence of a friend that he found the file on an old computer and kept submitting. He fought for his permission.

As an emerging independent filmmaker, I’ve recently acquired the rights to tell a story I think is powerful, and as a ghostwriter, I am trusted to tell people’s stories all the time. The responsibility of being given that level of permission is staggering and I always tell my clients how grateful I am that they trust me enough to grant me that permission. In these instances, permission can not be taken, it must be earned and then shared.

Oh, what a fascinating thing.

I can’t imagine my world without having read A Brief History. It made me courageous in my storytelling. James gave me permission. I can’t imagine the literary world without The Bronte Sisters, or George Eliot, or Phillis Wheatley. They found ways to skirt permission and create works that transcended their existence. But as I write this today, I wonder, seriously, how much permission do we really have? When is it okay to take permission and when do we need to find ways to maneuver more amiably?

This is one of the reasons I and so many other writers resort to using fantasy as our mode of operation. We do not have to "ask permission" if we write about beings who do not exist in the real world, or who have over-vigilant formal and informal political organizations working on their behalf.

It’s so nice to get to read inside the mind of a published author and your thought process on what you write and how. Your perspective and opinions are super key. I also learned a lot from this. Thank you!