Sitting beside Hanna in Norway, I didn’t know what to say. I’m not someone who is known to start conversations, but I can certainly continue them. Hanna is a writer and activist from Belarus and it was my first day of a week-long trip, sitting in a circle with writers and activists from all over the world.

When we began our conversation, Hanna told me that she wasn’t sure writing was enough anymore.

“I don’t know how much difference it makes,” were her words.

I was confused. Writing for me was everything, the only thing and writing itself—separate from any outcome—was enough to bring me some kind of fulfillment. But here was another writer, a poet and a playwright, telling me that what she wanted to accomplish with words just wasn’t enough.

This was mid-2024 and for the first time in my life, I questioned not just my own writing but the value of literature altogether. In a world fueled by capitalism and capitalistic values, what is literature’s place? What value do written stories have in a system that prioritizes production, efficiency and commodification?

It’s a complicated concept to unpack, so let me start by telling you what I mean by literature.

The word 'literature’ derives from Latin and means “writing formed with letters.” So technically, any writing can be considered literature. But that’s not the definition we’re working with today. I’m using the Romantic Era definition of literature, which can be described as writing stories with imagination that expresses some collective human truth or experience through beauty.

It’s a bit ironic (and intentional) that I’m using the Romantic Era as my reference point for literature. That Era stretched from the late eighteenth to the mid-nineteenth century and it gets its name because much of the writing (and art in general) was focused on individual emotion, the connection to nature and a type of sublime understanding of our existence. As flowery and romantic as this sounds, the writing of this period was rebellious. The Romantics wrote in this manner because they opposed the capitalistic systems of the time that reduced human life to how efficiently they could produce and how much they consumed. Those values were seeping into daily living and the Romantics wanted none of it, so they wrote.

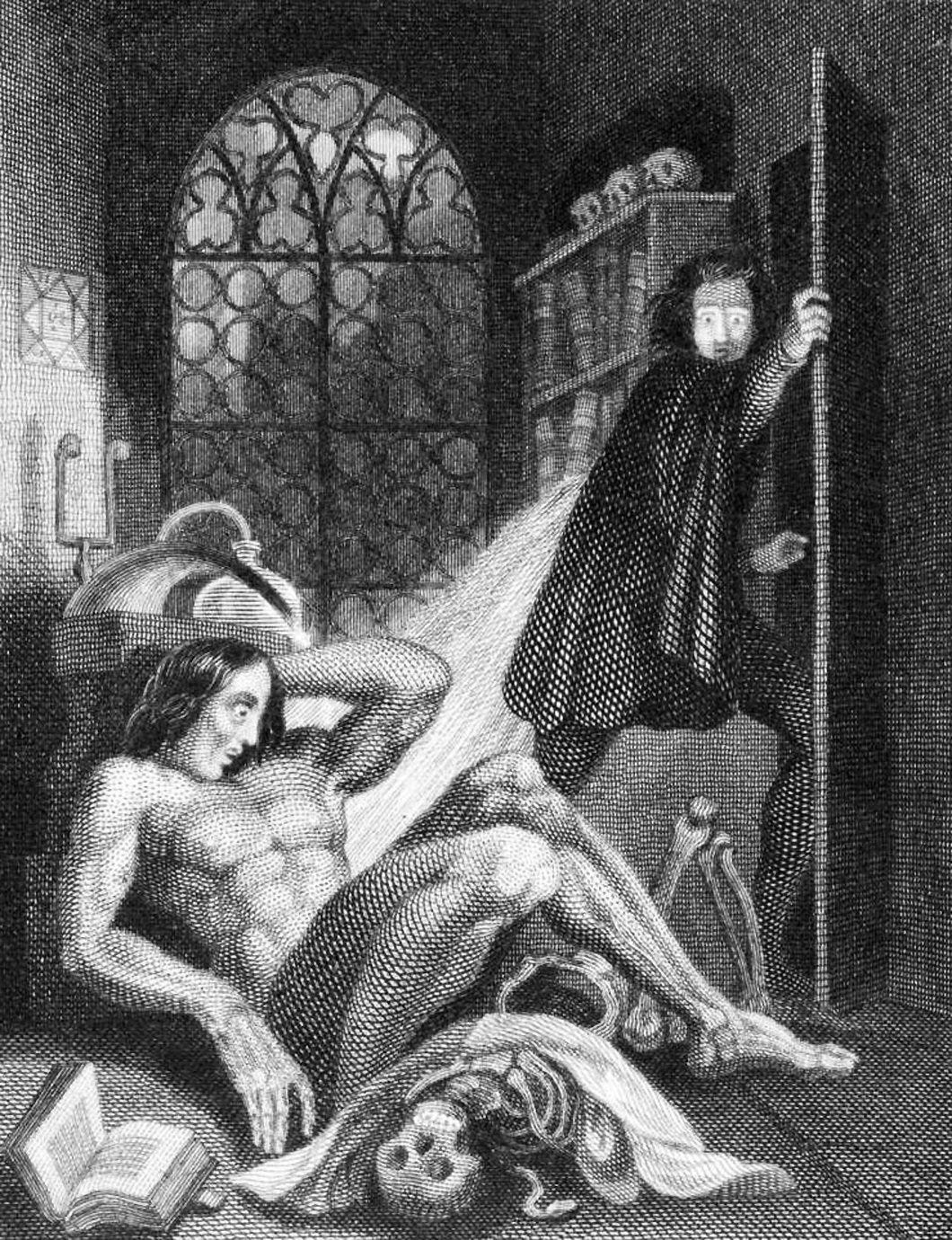

This is the reason Mary Shelley wrote Frankenstein. It was a warning against the prevailing dependence on science brought about by the Enlightenment. Through Frankenstein, Shelley used literature to force her generation to consider deep, existential questions about the soul of humanity and about what it means to be alive. In this way, Frankenstein represented resistance.

This is also the reason Jane Austen wrote Sense and Sensibility, Pride and Prejudice and her other novels. Austen’s literature criticized the broken social structures and moral values of the time through captivating stories of high society. Make no mistake about it, as entertaining as Austen’s stories had become, they were rebellious.

That gives us a clear idea of literature’s purpose during this time period. Shelley and the Romantics were writing to challenge conventional thought, to explore cultural themes of the day and encourage readers to do the same.

If we step back even further, before capitalism had a stronghold on Western society, we see literature play a slightly different but equally influential role. Because it is essential to remember that pre-capitalism, being an author was not something one made a living from. Writing was not a profession. Instead, authors wrote, or more specifically, earned their dollars writing, only from the funds bestowed upon them by the wealthy. Kings, princes and statesmen provided patronage to monks, philosophers, university teachers and even soldiers to tell their stories freely. The mass production of those stories for broad, public consumption was not the aim. As explained in Mises, The Anti-capitalist Mentality:

“The penniless man whom an irresistible impulse prompted to write had first to secure some source of revenue other than authorship…most of the poor authors lived from the openhandedness of wealthy friends of the arts and sciences…The courts were the asylum of literature.”

That meant that during this period, the value of literature was tightly connected to political and socioeconomic functions. Authors wrote freely, with the subject of their writing aimed at social and political ills of the time. Writing was a means of expressing and dispensing dissenting thoughts among the elites, the nobles, the aristocracies, and its influence on thought amongst those groups was profound. The church was often a target, as were corrupt monarchies, but this only represented a part of the purpose of pre-capitalistic literature.

When we analyze this a bit deeper, we see Milton didn't write Paradise Lost for profit. Milton came from a wealthy family and didn’t get a formal job till he was nearly 40 years old. For authors writing during Milton’s time and before, two things were important: first, the action of writing itself and its quality. Second, to influence the minds of the day and be remembered. The latter was particularly important because authors at the time were revered differently since literature was not something accessible to the masses. Most people couldn’t read so when authors like Milton wrote, it was in part to create a legacy that outlasted their lifetime and that meant they had to write something that was true to the human condition.

Okay, but that’s all historical. What about today? What is literature’s value today?

I’m thinking about Hanna again. Sitting in that circle, I heard her recite such beautiful poetry. Poetry that both moved me and exposed me to atrocities that even though I was aware, I previously had no personal connection to.

But Hanna is also an activist. My assumption is that she expected her words to not just stimulate my intellect and emotion, but to move me (and others) to action in the tradition of authors like Henrik Ibsen (The Doll House) or Harriet Beecher Stowe (Uncle Tom’s Cabin) or Upton Sinclair (The Jungle). Hanna was weighing the value of her literature by a preferred social outcome. If that outcome failed, then her writing must have felt irrelevant.

But in today’s social and cultural climate, I fear Hanna’s expectations might be too much. The value of literature today has been reduced to its commercial outcome, not in its ability to stimulate the mind, challenge thought and cause change. How many people bought that book? Was that book made into a film? What was the author’s advance? These are all markers of success today as determined by our current culture under capitalism. And because capitalism seeps through so much of our daily lives, all of those markers are actually valid and dare I say significant.

And because of those commercial determiners, I wonder if the intrinsic value of literature is lost. Do readers have the appetite to be moved by the written word so deeply that it changes their perception of something meaningful in their lives? Can they no longer read just to feel something? Or is it imperative that we pick up a book from Reese’s book club or the TikTok table to feel that what we have read actually matters?

I’m starting with readers because I often feel they get let off the hook. Readers are the people; the masses, while writers are the messengers; the minority. They’re the ones authors are hoping to inspire or impress with their words. If readers are no longer excited by books that push them to reflect, to feel inspired, but instead prefer books purely as a means of escapism, books that are often propped up by capitalist forces understanding that mass appeal is the goal, then what intrinsic or even practical value is left? Because if readers are reading to turn their minds off instead of activating their senses, that’s a big turnaround from centuries past.

I watched a BookTok video where the Influencer—someone with a large following because they read and recommend books—said that they mostly skim these titles. Another BookTok Influencer said they skip most of the prose and only read the dialogue. Does that sound like a society that’s reading to be inspired? Or have they in fact commodified literature to the point that its value feels diminished?

As authors, and I’m including myself in this criticism, how are we responding to this development? Are we only writing to be picked up by our dream publishers? Do we hope that one of these BookTokers will find our novel and promote it to their legions of followers? I wonder if the ability to truly shift cultural perception and behaviour, or simply to encourage someone to think deeply, is even possible anymore, or even something authors strive to accomplish? Are we obsessed with creating something beautiful or are we simply trying to sell books by any means necessary?

Let me be clear: I am someone who currently writes for a living and eventually hopes to write novels full-time. I, too, hope to sell millions of books so I’m not removing myself from criticism here.

I was raised in capitalism so this is unfortunately a large part of my mindset.

But my concern is that something is lost in literature when it becomes commodified in a capitalistic manner. I saw a video where a grade school teacher said her principal pulled her into the office and asked her to stop reading to her class and instead get them prepared for their state exams.

Umm, excuse me?

Are we not understanding the true value of picking up a book, reading the words on the page, and thinking critically about what the words on that page actually mean? Can we not draw a straight line from The Bell Jar to Girl Interrupted or The Bluest Eye to A Thousand Splendid Suns and see how literature can, at the very least, push us to understand ourselves just a little bit more intimately?

Part of me also wonders if authors should just be playing the game differently.

There’s an underground rapper named Mach Hommy. I’m willing to bet that 99% of you reading this right now have never heard of him. Yet, he sells the overwhelming majority of his projects directly to his fans for between $300-$7,000 for physical versions. He also limits the number of physical products he creates. He once sold 28 copies of an album for $999.99.

By playing the game, Mach Hommy is forcing his fans to value his art differently. He’s saying, not subtly, that if we are to create within capitalism, then these are his terms. Because if value is exclusively determined by commercial factors, cost being one of the most prominent, then let him be the one to set that value. And because that value is relatively high and counter to the current, common value set by the market, it dissuades casual fans from engaging and speaks almost exclusively to fans who would appreciate the art.

In some ways, Mach Hommy’s approach is brilliant.

When thinking about the value of literature, maybe if we priced it in this way, it would be viewed differently by consumers and inherit a much higher cultural value than it does today. What would it look like if I charged $300 for my softcover and $400 for my hardcover? Would that allow me to create precisely the type of deep literature my heart yearns for? And would that also dissuade casual readers from reading and set the expectation for a more profound literary experience?

This type of thinking feels like a trap. Yes, I want to make money because that’s the game, but I don’t want to make my book inaccessible to those kids in the classroom. Oh what a feeling it would be if there was no monetary profit to be gained from the literature that we create. Just words and the people to read them.

What would literature look like then?

By the end of my week in Norway, Hanna confessed that she found her love of writing again. Maybe love is the wrong word. I think maybe she recognized again that writing itself is the true victory, the true purpose and that literature will always hold a special place in her heart and the hearts of those of us lucky enough to hold a book in our hands.

Again, I have many thoughts on this subject, so I will say a few.

As a reader, even from an early age, I have always gravitated towards that activated/ challenged my mind. Cheap escapism never interested me. But that's just me. I want to be changed by a book! Even if it's just one line, one thought - I'll take it. I'm grateful.

As a writer, much the same way, those are the kind of books I want to be writing. Something that will make my readers think / rethink things. A story that would move them in a meangful way. (Yes, no pressure)

As for the money, I wouldn't want to sell books for $300-400 because then books/ reading will become a luxury for the rich. I wouldn't be able to enjoy books then.

But - it would be nice if writing was more appreciated, and compensated for. For example here, on Substack. Why do we have to sell some kind of a "value" instead of our hard work (our writing) being enough to get the monthly equivalent of a Starbucks coffee? So many of my wealthier friends wouldn't hesitate to spend the money on a good bottle of wine, but wouldn't pay for writing. I know you put your heart and soul to each of your posts. So do I. So why do we do it? Because when the world is as dark and as unkind as it feels right now, and one person responds to my post with "I have never read anything as beautiful as your essay. You have opened my heart to another perspective" I feel that maybe, just maybe, I have helped moving us a touch closer to kindness. And it's the best feeling in the world. (I just wish I didn't have to paint walls to finance it...)

Thank you for your writing Kern! Even before I became a paid subscriber I always appreciated your work. I always look forward to reading you. Happy holidays!

I think the biggest impact has been the consumerism and capitalism. The audience of today are hardly "readers" anymore. Insta and YT has turned them into brainless consumers with a 3 second attention span. Literature, both long and short format, can't currently compete with that.

In addition, the "hustle culture" arising from capitalism tells people to focus on their own grind to rule the world with bucks, which also means ignorance of the soul, which, according to me, is a prerequisite for becoming a reader.

P.S. Amazing post + the arrangement.